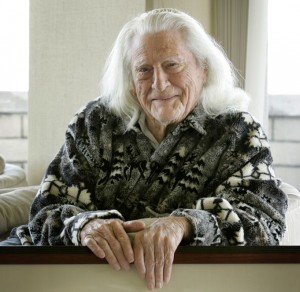

The Original Tropical Architect

Alfred Browning Parker is “The Original Tropical Architect.” in order to realize why this is so, a bit of historical prospective is required. After spending his childhood growing up in Miami he went on to attend the school of architecture at University of Florida (UF). There he meets the schools director Rudolf Weaver who became his principle mentor. While in school, Parker discovers Frank Lloyd Wright through the magazine Architectural Forum in 1938. Keep in mind that in 1936 Mr. Wright designed the first of the iconic “Usonian” Houses. These houses incorporated sustainable design concepts of solar heating, natural cooling, radiant floor heating, day lighting, with a strong visual relationship to the outdoors.

A few years after his introduction to the work of Wright, Weaver brought the work of Dr. John Gifford, a pioneer ecologist and professor at the University of Miami (UM), to his attention. Gifford’s ecological philosophies resonated with Parker and on his return to Miami after graduating from the UF he introduced himself to and attended his classes at the UM. John Gifford eventually become Al Parkers father-in-law.

Al Parker opened his “workshop for the practice of architecture” in 1941, his work reflecting the influences of Weaver, Wright and Gifford. Parker went on to become Florida’s foremost modernist architect, whose work reflected sensitivity to the Florida environment. Building in harmony with the climate and landforms, using local building techniques coupled with use of indigenous natural materials. The result was an honest architecture that was designed and built for its environment.

Long before “Green Architecture” became the word du jour, Al Parker embraced the principles of a south Florida vernacular architecture. Architecture “of the place” where it is built, rather than one that is created purely for stylistic purposes. South Florida’s environment is hot, humid and wet, infused with tropical vegetation. These characteristics were best expressed in his houses that open to the outdoors, from the interior, through an exterior wall of hinged, operable wood louver, persiana doors, on to large covered verandas, to a lush tropical garden beyond. With large covered verandas protecting the interior from monsoon like rain fall, allowing the persiana doors to remain open to a cooling breeze.

Designing an architecture that responds to the sun, wind and environment only makes sense. These basic building blocks of “sustainable architecture” were expressed in the vernacular architecture of the Seminole Indians’ “Chickee” hut shelters and that of early European settlers’ Florida “Cracker” houses. It’s back to the future, today these same principles are now espoused as the new “green” vision. Along with the South Florida’s indigenous peoples, early settlers and Mr. Wright who came before him, Al Parker’s work reflects these principles and inspired the next generation of young modernist Florida architects who aspired to follow his lead creating an organic architecture of and for South Florida.

“Make it useful and make it beautiful. That is all you need to know about architecture.” These are the two main things Mr. Parker learned from his principle mentor Rudolf Weaver. The design philosophy by which he aspired for nearly 70 years.

The Architecture of Alfred Browning Parker, Miami’s Maverick Modernist by Randolph C Henning was recently published by the University Press of Florida. This monograph beautifully depicts the man, his work and his philosophy.

About the Author:

William Hoffman is an architect & LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Accredited Professional who designs and builds sustainable new homes & home renovations.

Contact info: Phone 954-561-1642 or through HoffmanArchitecture.com

Photo Credit: Alfred Browning Parker, June 2007. Photo by Doug Finger, Gainesville Sun, used with permission

Recent Comments